In March, as the COVID-19 pandemic gained a visible foothold in New York City and infected hundreds of thousands of residents, Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian faced a task unlike any they had encountered before.

How would they quickly establish a reliable diagnostic testing program to identify patients and healthcare workers who had been exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, amid a rapidly escalating public health crisis? To accomplish such a task, the institutions would have to prove that newly developed commercial tests accurately diagnose the coronavirus, while simultaneously expanding the operations and hours of pathology laboratories to handle an influx of patient samples.

In this environment, Weill Cornell Medicine’s medical laboratory directors and scientists developed a COVID-19 testing program that, when launched on March 11, analyzed 300 clinical samples a day, in addition to conducting non-COVID related tests. Some seven weeks later, those same laboratories can process up to 2,000 COVID samples daily and are operational 24 hours a day, so that physicians have the most accurate information to guide treatment for suspected COVID-19 patients who come to Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

“Our expanding testing capabilities have made a major impact on New York’s epidemic, as we assiduously work to identify patients who are ill from COVID-19,” said Dr. Massimo Loda, chair of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and pathologist-in-chief at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “I’m extremely proud of the dedication and creativity of our microbiology, molecular pathology and central laboratory teams, who have worked around the clock to bring these advances to our patients.”

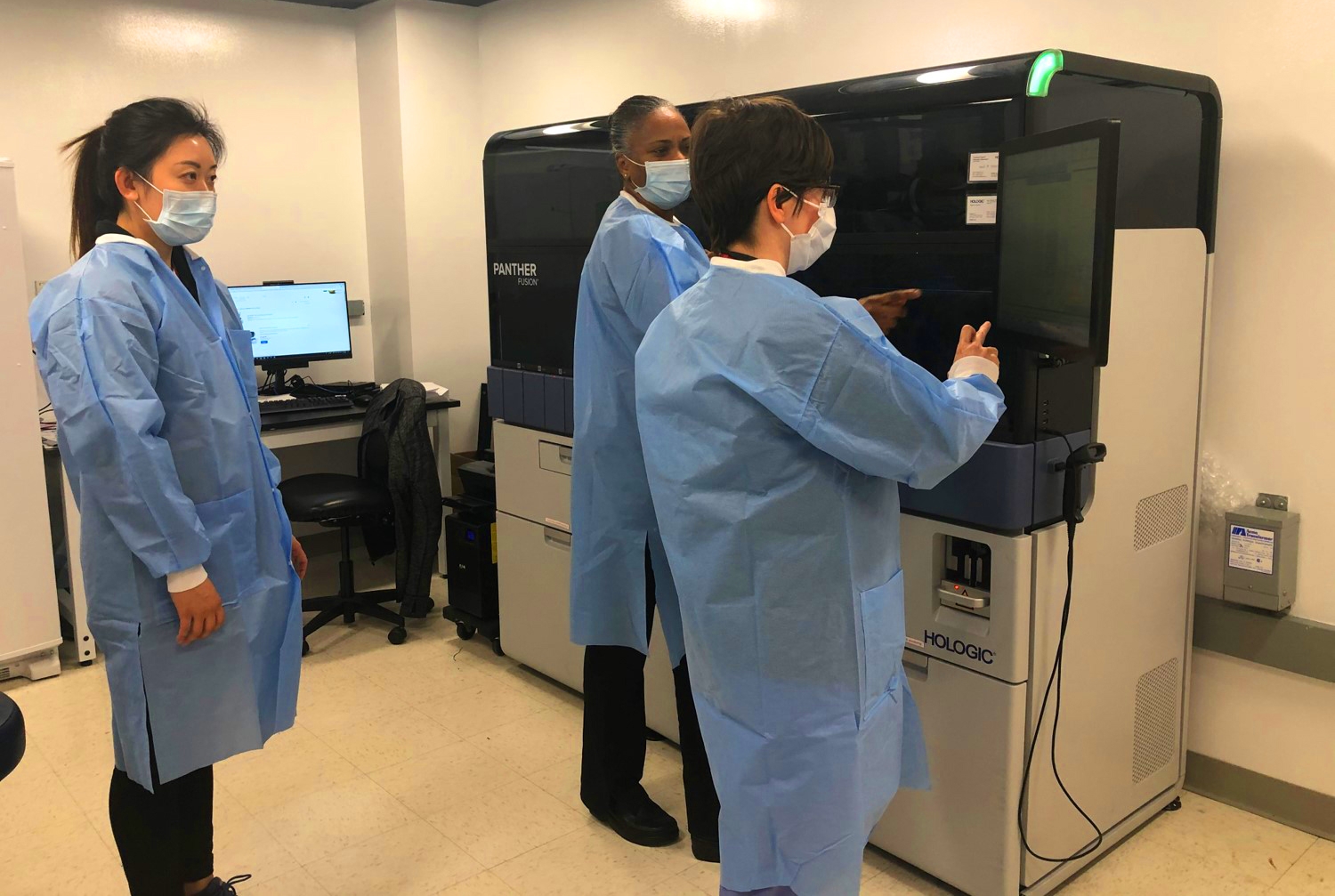

Laboratory technologists and accessioning staff at Weill Cornell Medicine. From left: Aaron Thailla, Shanaya Mitchell and Marlin Romero.

Public health officials say readily available diagnostic COVID-19 testing is one of the most powerful tools in the healthcare arsenal to combat the global pandemic. The challenge that faced Weill Cornell Medicine, NewYork-Presbyterian and peer medical institutions around the country was how to build a large-scale testing program for a novel coronavirus from the ground up.

Enter Dr. Melissa Cushing, director of clinical laboratories and vice chair of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Collaborating closely with her colleagues in the Department of Pathology’s Clinical Microbiology and Molecular Pathology Laboratories—among the first labs in Manhattan approved by the state to perform in-house testing—Dr. Cushing and her team set out in early March to establish a testing program using a diagnostic method called real time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, or rRT-PCR.

“This testing approach has been used for decades to diagnose bacterial and viral infections, as well as some genetic disorders, and is considered the gold standard in detecting COVID-19 because it is highly sensitive and specific,” said Dr. Cushing, who is also a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The testing process begins with a swab of a patient’s nasal cavity that is then submitted to the pathology laboratories for diagnostic testing. For Weill Cornell Medicine’s initial iteration of the rRT-PCR test that launched on March 11, a medical laboratory scientist first deactivated the virus so the patient sample was no longer infectious. Next, the laboratory scientist extracted the virus’s genetic material and added it to a reactive chemical developed and supplied by Altona-Diagnostics, which Weill Cornell Medicine clinically validated the weekend of March 7-8. The sample was then inserted into a specialized machine called a thermal cycler, which through repeated heating and cooling generated many copies of a viral gene. If at the end of the cycle the viral gene was present, the chemical, or reagent, emitted light at a specific fluorescent wavelength, indicating a positive test. Samples without viral material were tested simultaneously to ensure that the test results are accurate. Initial capacity started at 290 tests per day, with results in about four hours.

Over the next several weeks, the pathology team clinically validated additional reagents from other suppliers—a process that typically takes six or seven months but was expedited because of the pandemic’s magnitude and severity. On March 30, the Weill Cornell Medicine team validated a new instrument and reagent from the pharmaceutical company Roche that expedited the testing process by automatically performing all of the laboratory steps and using the same viral genome copying process.

On April 6, the team launched a new rRT-PCR rapid test from supplier Cepheid for urgent testing, with results within an hour or two. This test has been used to assess patients who come to NewYork-Presbyterian’s Emergency Department, as well as pregnant women in labor and preoperative patients. And on April 15, the team validated and implemented a fourth test; together, the four platforms expanded capacity to over 2,000 tests per day.

To accommodate the expanded testing, Dr. Cushing and her team added a third shift to the laboratory schedule, mobilizing licensed medical laboratory scientists and medical school volunteers who have experience in molecular testing and microbiology, and qualified for the national requirements to perform laboratory testing.

“The commitment and enthusiasm of our community to assist us has been nothing short of extraordinary,” Dr. Cushing said.

With the curve in new infections and hospitalizations now appearing to flatten, pathology leadership have turned their attention to antibody tests that reveal whether healthcare workers and patients have been exposed to COVID-19 by detecting evidence of an immune response. (Scientists do not yet know whether having antibodies means that one is immune from COVID-19 reinfection.) Weill Cornell Medicine can currently administer 2,000 antibody tests a day, with capacity expanding to a few thousand a day in the coming weeks. With that increased capacity, Dr. Cushing expects that Weill Cornell Medicine will be able to provide antibody testing to healthcare workers, patients who were treated at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, and to the general public.

“People may feel more comfortable being around family—especially if their loved ones have a COVID risk factor—if they know they’ve already been infected and developed antibodies,” Dr. Loda said.

Pathologists have also been investigating whether a component of blood, called plasma, taken from a patient who has successfully recovered from COVID-19 and transfused into someone who is currently infected, can speed up recovery and improve outcomes. Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian are participating in an international, multi-site clinical trial that will investigate this experimental therapy.

“These testing and treatment efforts are crucial in our fight against the COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Cushing said. “We are so proud of what we’ve accomplished in just two months, and working tirelessly to advance these promising lines of inquiry for the betterment of our patients in New York City and beyond.”