T-cells taken from the blood of people who recovered from a COVID-19 infection can be successfully multiplied in the lab and maintain the ability to effectively target proteins that are key to the virus’s function, according to a study from Children’s National and Weill Cornell Medicine investigators published by Oct. 26 in Blood.

“We found that many people who recover from COVID-19 have T-cells that recognize and target viral proteins of SARS-CoV-2, giving them immunity from the virus because those T-cells are primed to fight it,” says Dr. Michael Keller, a pediatric immunology specialist at Children’s National Hospital, who led the study. “This suggests that adoptive immunotherapy using convalescent T-cells to target these regions of the virus may be an effective way to protect vulnerable people, especially those with compromised immune systems due to cancer therapy or transplantation.”

Based on evidence from previous phase 1 clinical trials using virus-targeting T-cells “trained” to target viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus, the researchers in the Cellular Therapy Program at Children’s National hypothesized that the expanded group of COVID-19 virus-targeting T-cells could be infused into immunocompromised patients, helping them build an immune response before exposure to the virus and therefore protecting the patient from a serious or life-threatening infection.

“We know that patients who have immune deficiencies as a result of pre-existing conditions or following bone marrow or solid organ transplant are extremely vulnerable to viruses like SARS-CoV-2,” says Dr. Catherine Bollard, senior author of the study and director of the novel cell therapies program and the Center for Cancer and Immunology Research at Children’s National. “We’ve seen that these patients are unable to easily clear the virus on their own, and that can prevent or delay needed treatments to fight cancer or other diseases. This approach could serve as a viable option to protect or treat them, especially since their underlying conditions may make vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 unsafe or ineffective.”

The T-cells were predominantly grown from the peripheral blood of donors who were seropositive for SARS-CoV-2. The study also identified that SARS-CoV-2 directed T-cells have adapted to predominantly target specific parts of the viral proteins found on the cell membrane, revealing new ways that the immune system responds to COVID-19 infection.

Current vaccine research focuses on specific proteins found mainly on the “spikes” of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The finding that T-cells are successfully targeting a membrane protein instead may add another avenue for vaccine developers to explore when creating new therapeutics to protect against the virus.

The Cell Therapy Program is now seeking approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a phase 1 trial that will track safety and effectiveness of using COVID-19-specific T-cells to boost the immune response in patients with compromised immune systems, particularly for patients after bone marrow transplant.

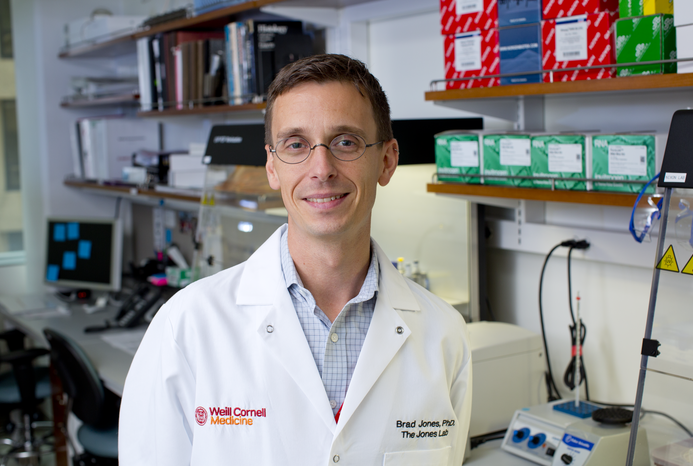

“This work provides a powerful example of how both scientific advances and collaborative relationships developed in response to a particular challenge can have broad and unexpected impacts on other areas of human health.” says Dr. Brad Jones, an associate professor of immunology in medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Weill Cornell Medicine and co-author on the study, whose lab focuses on HIV cure research. “I began working with Dr. Bollard’s team several years ago out of our shared interest in translating her T-cell therapy approaches to HIV. This put us in a position to quickly team up to help develop the approach for COVID-19.”

A version of this story first appeared on Children’s National’s Newsroom.